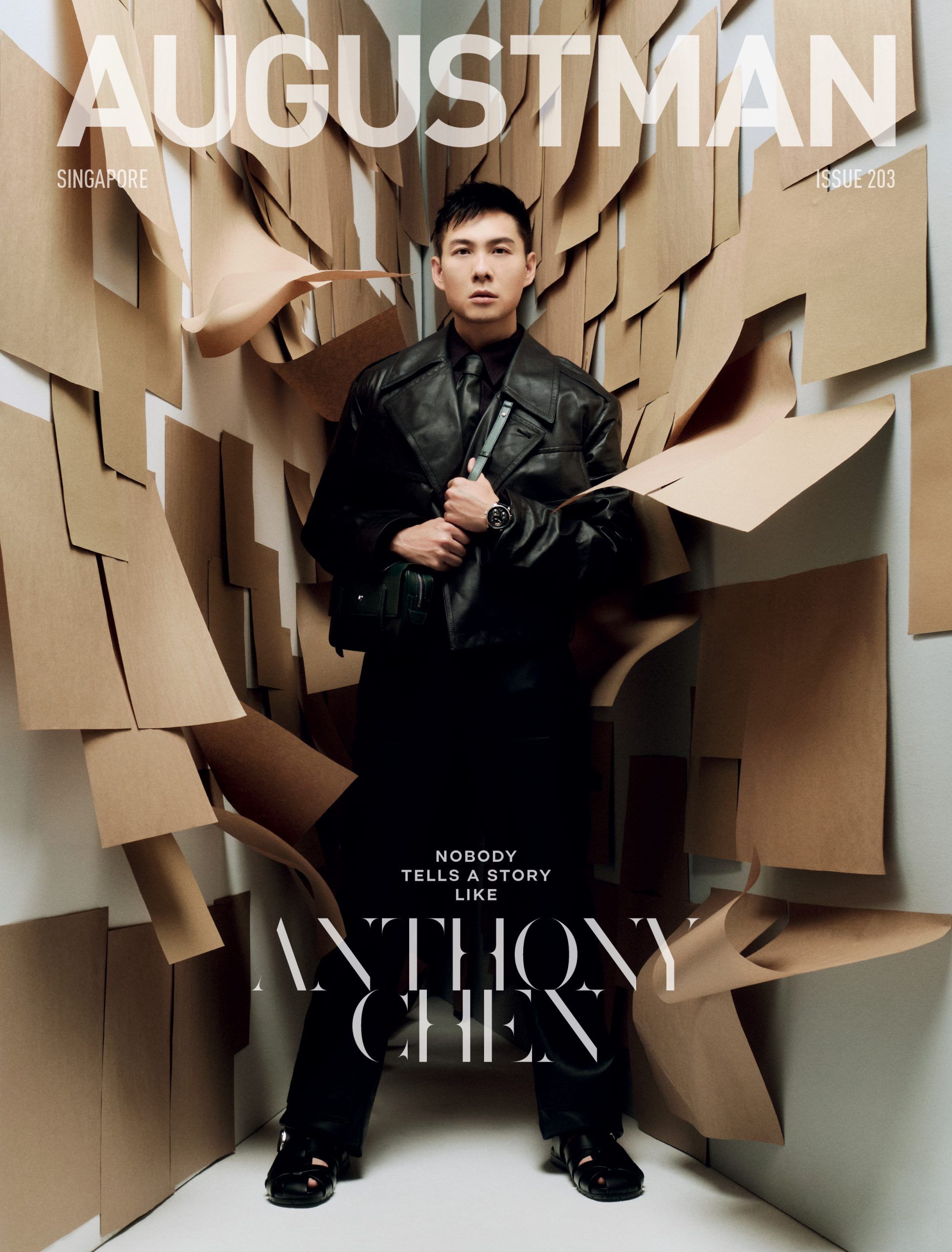

One could say that Anthony Chen is a once-in-a-generation talent. After all, the filmmaker is the only Singaporean, thus far, to win the prestigious Camera D’Or at the Cannes Film Festival, back in 2013. Since then, the closest we’ve come is this year, when Chiang Wei Liang’s Mongrel received a Special Mention Camera D’Or Prize. Boo Junfeng’s profound study of the death penalty, Apprentice, was only screened under the Un Certain Regard programme. The proof for the above notion is in the pudding — or rather, in the prize.

But Anthony disagrees. “For a country of 5.5 million people, we have so much talent. In the film industry, we have (Boo) Junfeng, Kirsten (Tan), Raja (K. Rajagopal).” Having worked in the film and television industry before, I am inclined to agree with him. Singapore’s investment into the industry has borne fruit, with some visionary actors, scriptwriters, and directors entering the fold.

However, Anthony has something that not many within Singapore’s talent pool have.

I’ve met Anthony four times in my life, including this interview. Every conversation was marked by creative discussion – Anthony, I would discover very quickly, is a natural storyteller. He does not need the bells and whistles of genre to tell a good story. Some storytellers need spectacle – explosions, dragons, or car chases – to lend their story weight. Anthony does not.

Instead, he finds stories in human emotion, in the everyday. He finds profundity and gravitas in conversation. He finds meaning in the unspoken. Ilo Ilo is a fantastic study in what people say to each other, and what people leave unsaid. Its subtext is just as powerful as the text. Just watch closely at how Terry behaves after witnessing Jiale getting caned in school.

And Anthony continues to wield that power in last year’s Drift. Cynthia Erivo’s Liberian refugee Jacqueline wears all the trauma of her past in the subtext.

She wears it like the clothes on her body, and we can sense it even in those brooding shots of her facing the ocean. In her interactions with Alia Shawkat’s Callie, there is so much of Jacqueline that we can glean both in the things she says to Callie, as well as in the little details — subtle looks, the information she withholds during their first couple of interactions, the unspoken deepening of their friendship. Speaking of the unspeaking, the ocean can also be argued to be its own character — as Jacqueline sits by the Greek shores, looking at the ocean that forms the gulf between her and her native Liberia, there is an unspoken conversation between them about ideas of home, belonging, and family. Jacqueline sees herself and the many uncertainties of her life in the roiling waves. Anthony simply lingers over the ocean in select shots, letting its ebb and flow organically form meaning in the viewer.

It’s a difficult skill to master, even in veteran directors. Earlier scenes need to earn those moments, to give those shots meaning. You need to get the framing right, you need to show how the characters embody those moments — their expressions, their body language needs to carry the emotional weight and gravitas of the visual. Those scenes in Drift carry the mark of a very confident director.

And then there’s Anthony Chen the screenwriter, who is an astute observer of the human condition. Last year’s Un Certain Regard screening in Cannes, The Breaking Ice (directed and written by Anthony), was an incredible study in loneliness. Haofeng, who works in the finance industry in Shanghai and whose wealth has failed to bring meaning to his life, goes to the icy cold city of Yanji in northern China for a friend’s wedding. There, he meets Nana and Xiao, who are awed by his city life and his job. Even though he gets intimate with Nana, he still feels a disconnect from her. There is a powerful scene in which the three of them go to a club, and Haofeng tells the other two to go dance. Left alone at their table, Haofeng begins crying, his isolation and failure to truly connect with the people around him finally overwhelming him.

I asked if this was how he chooses the movies he writes or directs — these moments of deep, raw emotion, where the human condition is laid bare for the audience.

“It’s not a choice. I don’t set out as a filmmaker with that intention,” he replies, before noting: “But I realise more and more that every film is such a personal experience. It’s impossible to remove my work from my own emotions. Everything becomes tightly interwoven together. When you see those naked, raw, delicate emotions in my films, it’s because I’m baring my soul and giving so much of myself.”

Because of this, Anthony chooses his projects carefully. “It’s never just a job for me. There’s so much heart and soul and emotion to everything I do. In some projects, my colleagues would tell me, ‘This isn’t the kind of thing that’s worth killing yourself over,’ but that’s the way I work.”

He adds: “Every time I take something on, I always need to find a personal connection. All the stories I’ve told as a filmmaker, whether it’s scripts that I’ve written, or written by someone else, or adaptations of books I’ve read, they’ve moved me, or I find a strong, deep emotional resonance in them. Otherwise, it’s impossible for me to make the film or tell the story.”

It’s a streak I’ve seen in the truly creative — artists and visionaries with an unyielding need to tell a story or create a work that carries a profound truth about existence and the human condition. The Singaporean system very rarely rewards such individuals.

Anthony agrees: “It can get very lonely. We’re in a country and society driven by pragmatism, and I’m driven by emotions. Sometimes it gets lonely because people around me don’t quite understand why I do what I do.”

On the other side of the coin, it can be challenging to work with Anthony — something the filmmaker himself admits. “I realised I get very demanding and uncompromising of myself, my team, and my actors.”

I understood — great work always comes at a price. Anthony shares: “A lot of times I push people to their limits. I remember the last shot we did of Wet Season was a simple close-up of Yann Yann (who played the lead role, Ling) just looking up at the sky, the sun coming out of the clouds. We took 23 takes. For me, it wasn’t just a cheery smile, just a happy ending. The smile needed to have baggage. It needed to be bittersweet. It cannot be simplistic. It needed to encapsulate her journey.”

I asked where this passionate, singleminded spirit came from, and Anthony replies with a laugh: “It’s because I’m an Aries.” It made me think of another filmmaker who shares Anthony’s birthday (18 April) and relentless zeal — Eli Roth. Both have an acute understanding of the human condition, only Roth uses it to create unforgettable horror movies.

The truth is, if we don’t have individuals like Anthony, Singaporean cinema cannot grow. Individuals like Anthony drag us out of mediocrity, and push the envelope in the kind of stories we can tell. But we need so much more for Singaporean cinema to really evolve beyond what it is now.

Anthony notes: “Our filmmakers have come of age, but our audience largely has not. We have very strong funding structures from IMDA and the Singapore Film Commission that has helped to nurture filmmakers and helped to facilitate their short films and features. But now it’s no longer just on the film industry or the government. If we really want to see Singaporean cinema make its mark on a global level, it needs to be a national effort. Look at South Korea. The public at large needs to be willing to support the industry — whether it’s investing in these films, or even just in providing filming locations. Open your doors to filmmakers.

A lot of people say, ‘No, you cannot shoot in my house, you cannot shoot in my office.’ Even something as simple as that can make a difference.”

He continues: “I feel, as Singaporeans, we suffer from this weird, perverse, possibly post-colonial inferiority complex. Even when we have good work made by local talent, the public isn’t there to support it. I feel we need that for a more sustainable film ecosystem. I was in South Korea recently for a film festival, and the public was there in strength to support their local films. They want their work and their culture to be seen by the world. They’re proud. And Korean films don’t just do well outside of Korea. Domestically, there’s very strong support.”

Anthony is fast becoming an auteur — a filmmaker whose works are so thematically and stylistically distinctive that it is hard to separate the work from its creator. Just as you can immediately tell, from style, tone, and subject matter, a Christopher Nolan film, a Wes Anderson film, or a Taika Waititi film, there are burgeoning signs of Anthony’s distinct storytelling signature in his body of work.

But that can only happen if we, as a people, collectively support the many talented filmmakers we have. And if we want to support trailblazing filmmakers who hold a mirror to society, who investigate the human condition in an intelligent, emotionally mature manner, we need not look further than Anthony Chen, the master of text and subtext.